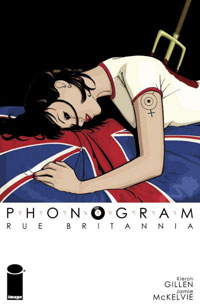

Phonogram: Rue Britannia

The creator bios for Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie concede that neither of them is technically a “young person” anymore. So what does that say about someone actually too old to get most of the neo-nostalgic pop-culture references that permeate the magical and musical story of Phonogram: Rue Britannia?

The creator bios for Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie concede that neither of them is technically a “young person” anymore. So what does that say about someone actually too old to get most of the neo-nostalgic pop-culture references that permeate the magical and musical story of Phonogram: Rue Britannia?

It’s OK; I can take it. I think.

In my defense, part of the problem is that I’m a yank, so the Britpop scene that serves as the touchstone for the characters and their story was mostly an ocean away. But that’s not really an excuse for someone who was in touch enough with British music to do a college radio show in 1986 that was all about the latest cool stuff from the UK. But as college, the Smiths, partying, and the Housemartins receded into my past, I stopped paying much attention to popular music, so most of the bands referenced are just familiar names with no hooks attached to them.

Which actually puts me in a good position to appreciate some of what these think-they’re-no-longer-young creators are trying to convey in this story. The music of their youth (a nostalgic homegrown reaction to the grunge rock coming from the States) has passed into history as well, and the philosophical question of whether it really meant anything (and if not, what it didn’t mean) isn’t all that hard to grasp.

Gillen and McKelvie were thoughtful enough to include a rather extensive glossary at the back of the book, explaining who was who, and a bit of what was what. They assert that you don’t need to know any of these specifics to figure out what the characters are talking about and follow the story, and I can confirm that’s generally true (though I didn’t actually need them to explain who Joy Division were and what London of ‘77 was about, thanks). But I think the book would resonate much more strongly with someone who, say, recognizes the album covers that the chapter dividers are based on, and can personally agree (or not) that Kula Shaker sucks.

The book follows an unapologetically affected 20-something phonomancer (a magician who uses music as the source of his power) through an existential crisis. Among other things, it seems that someone is tampering with the goddess associated with his origin as a mage, with the alarming development that he finds himself liking bands that he knows he has always despised. I’m trying to imagine absently humming along with a Guns N Roses song, and yeah… it’s a creepy feeling. He goes on a spirit quest to figure out what’s going on, and what - if anything - to do about it. Not exactly a page-turner, but interesting and entertaining.

The book follows an unapologetically affected 20-something phonomancer (a magician who uses music as the source of his power) through an existential crisis. Among other things, it seems that someone is tampering with the goddess associated with his origin as a mage, with the alarming development that he finds himself liking bands that he knows he has always despised. I’m trying to imagine absently humming along with a Guns N Roses song, and yeah… it’s a creepy feeling. He goes on a spirit quest to figure out what’s going on, and what - if anything - to do about it. Not exactly a page-turner, but interesting and entertaining.

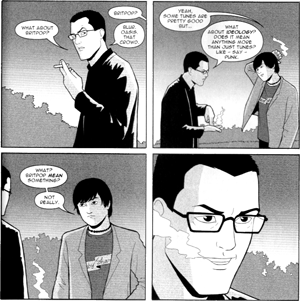

McKelvie’s art is endearing to look at, and perfectly suited to a story about a scene and a time of life in which youthful good looks are de rigueur. All of the characters look like they’ve been screened by central casting and/or the record label for audience appeal, with stylish hair and disarming smiles, but each with a distinct look and personality, and a basic grounding in reality. A cute reality. Even when the dialog meanders into the metaphysical and the setting into the surreal, there’s never any difficulty following the clean and clear art.

Back in the punk days, rocker Tom Robinson used to invite his audience to join him on the chorus of his anthem “Glad to Be Gay”, saying that you didn’t have to be gay to sing along… “but it helps”. Likewise, you don’t have to be an slightly-aging Britpop aficionado (or even an earnest music fan) to get into Phonogram. But I’m sure it’d help.